Posted by Mike Butler

on Wednesday, 30 November 2016

·

Electric Brass Records EBR006

Sometimes it seems that Spaceheads are such a self-contained unit, they need nothing else. Put simply, Andy Diagram covers the melody and Dick Harrison takes care of the rhythm. With such a clear allocation of roles, and an equally unambiguous objective – to storm the sonic boundaries – Spaceheads have been active for some quarter of a century and, until the ideas dry up (and there’s no sign of that), there seems no reason for them to stop doing what they do. The press release, with unkind justice, refers to Diagram and Harrison as ‘ancient astronauts’. Here they come to earth in a graceful landing.

Their last, A Short Ride on the Arrow of Time, proposed a jaunty excursion through space and time, just like the title said. Laughing Water is just right too, for music that is consistently adventurous and witty. ‘Be Calmed’, with its found sounds (someone is playing with the dial on an analog radio) is like a travelogue posted from the poolside of some luxurious continental hotel, with the guests too blissed to stir. Recording for the album, so the credits inform, began in Geneva in 2005 and finished in Cheshire in 2016. Actually much of the set has a meditative quality, presumably the Swiss counterpart to Norwegian pastoral. Music as individual and spontaneous as this is uncommonly open to the spirit of place. The passing siren, the last sound heard on the album, has a definite Swiss feel.

But wait. Something has happened betwixt and between A Short Ride on the Arrow of Time. Laughing Water contains a sterling contribution from bassist Vincent Bertholet (of Orchestre Tout Puissant Marcel Duchamp), which gives the grooves a new limber elastic resonance. Otherwise, Dick Harrison’s beats are as astringent as ever, and Diagram’s flow of melody – utilising trumpet, loops and samples – still continuous and inexhaustible. And the collective chant contributed by friends on ‘Machine Molle’ – “Everybody needs a piece of the world to find peace in the world” – is at one with the Surrealists’ notion that human society can only recreate itself through joy. Here Spaceheads depart from the spirit of our mean and fearful times. ‘Quantum Shuffle’ and ‘Pedalo Power’ are characteristically dance friendly. This is social music for Zurich and Manchester Dadas, by way of Geneva, but absolutely everyone is welcome to join the party.

spaceheads.co.uk

Posted by Mike Butler

on Thursday, 27 October 2016

·

I haven’t done this (blogged) for a while, and can only plead major life changes (marriage, migration) and my sad conviction that nobody has time left over from tweets and Facebook to blog anymore. Still, it’s good to keep my hand in, so here, thinking of a quick and easy way to increase the sum of human happiness, is a round-up of films on youtube which have lately taken my fancy.

Made in Heaven

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ueB5EcWV_VU&t=1378s

An attractive bit of fluff about an attractive bit of fluff from 1952, starring Petula Clark. The plot revolves around the Dunmow Flitch. It hadn't previously registered what a Dunmow Flitch was, despite a listen to the Dick Miles album of the same name, which goes to show that enjoyably lightweight old films can be more educational than folk song narratives.

Fame Is The Spur

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E9EIFt5DvDQ&t=245s

Labour politicians were weasels even back then. Michael Redgrave was an interesting fellow. A natural rebel, and drawn to edgy roles, sometimes to make the world a better place and sometimes for entertainment's sake. I’ve seen him in something else lately. Oh yes, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, but that was a DVD from the library, so outside my remit here.

I See a Dark Stranger

A cross between The 39 Steps and Odd Man Out and every bit as good as the description might suggest. Some of the Irish characterisation is a bit quaint, but the young Deborah Kerr is at least as radiant as the young Ingrid Bergman.

Midnight Episode

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YloTDTr7xM

With Stanley Holloway as a canny low-lifer who stumbles onto a murder. The story is a cut above your average musty thirties British mystery hokum. The reason why is contained in the credits, and easy to miss in small print: 'Based on a book by George Simenon'.

The October Man

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fx6XpkFaZg

A dark study of small-town alienation. See also Town on Trial – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tLqumM8L8A – a homegrown Bad Day at Black Rock. I rejoice in anything with John Mills in it. It's possibly a form of homesickness.

The History of Mr Polly

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=411B8AI1mOk&t=447s

See above. For all its gentle charm, it seems to me that this adaption of the H.G. Wells book is quite profound about the human condition (albeit the male, lower middle-class, Edwardian branch).

Child in the House

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oyWxc49LzUY&t=104s

On the same theme as The Fallen Idol – that fateful moment when innocence turns to knowledge, and subsequent disillusionment – and it seems to me the better film. (On the subject of Carol Reed flops, I came to A Kid for Two Farthings – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XnJfc_0Ihk – too late and too jaded to be much moved, though the period charm cannot be gainsaid.)

The Rocking Horse Winner

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KqG19zEKQ-g&t=967s

The supernatural allied to a strong anti-materialist message. Brilliant, just brilliant. All lingering prejudice against Valerie Hobson (mostly to do with Jean Simmons’ disconcerting metamorphosis into V.H. in Great Expectations) has vanished. Also stars John Mills. That’s the gilt-edged guarantee.

Cash on Demand

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PUaEQU327i4&t=155s

As good a Hammer and as good a heist, and as clever a reworking of A Christmas Carol as any I've seen.

So Long at the Fair

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVQG_UgM60U&t=22s

Here’s a plot that is perennially intriguing: ordinary couple do ordinary things –here a brother and sister arrive in Paris for the Exposition Universelle in 1889 – only one party disappears, and everybody is in flat denial that the party ever existed; protagonist doubts sanity, etc. It was used, in another context, in The Phantom Lady, a noir in which Elisha Cook Jnr does a manic Gene Krupa turn, and whose fate oddly mirrors its plot in that no-one has seen it or knows of its existence. Anyway, there’s a satisfyingly plausible explanation for the mystery here (The Phantom Lady has some hokum about a mad criminal genius). Jean Simmons makes a fetching damsel in distress, David Tomlinson is winningly personable (after Made in Heaven, I’m going to be keeping an eye on David Tomlinson), and only Dirk Bogarde’s quiff strikes a jarring note.

The Kidnappers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P1r-yEwGFo8

I actually remember watching this on some blessed Sunday afternoon of old. It was a gem then, and remains so today. But how easy it is to lapse into Presbyterian cadences after a viewing. The characters talk like that easily and plausibly. I like, "I don't believe grandfather is truly a dog-eater." Truly, this was the movie that raised the bar on naturalism in child actors. But it's the naturalism of all concerned, including the grown-ups, that saves

The Kidnappers from sentimentality and turns it into a saving statement of humanity.

The Long Memory *

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42UlvRYY79o

John Mills as the brooding outsider again, and a convincing candidate for Britain's Jean Gabin. That is, he shouts wronged, misjudged and doomed.

The Long Memory shows how romantic angst crossed the channel from fog-bound

Quai des Brumes to the unforgiving estuary landscape of Kent. How dreary and magical Northfleet looks; how stark and deserted Gravesend is. Kent natives

did go around singing traditional songs in 1953 (a few of the original old-timers were still around then), but how many were effectively avenging angels, I don't know. The stretchers in the plot can be excused by the film's existentialist aims.

The Long Memory is the work of Robert Hamer, the gifted director of

It Always Rains on Sunday and

Kind Hearts and Coronets, who, as an alcoholic homosexual, knew a thing or two about wronged, misjudged and doomed outsiders.

* NB This video has been removed because of copyright infringement.

We would not look upon its like again were it not for the dedication and discernment of youtube provider Dubjax (ten out of the twelve films above are Dubjax revivals). The Dubjax site keeps getting pounced upon by youtube's copyright infringement police, with the films removed and reconsigned to oblivion. So full credit to Dubjax, and catch them while you can. Dubjax has recently downloaded a fresh cache of musty masterpieces...

Posted by Mike Butler

on Wednesday, 10 August 2016

·

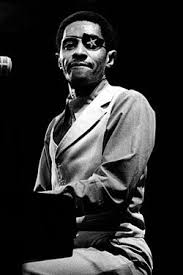

I was eighteen years old, new in London, and eager for blues and related art forms, when I was lucky to wander into the 100 Club on Oxford Street, in, I think, October 1977, to see the New Orleans pianist James Booker. ‘Lucky’ is an understatement. I had the night pegged as the gig of my life at the time, and nothing I’ve seen since has knocked it off its pedestal. I knew Dr John - In the Right Place was already a firm favourite - and I dug ‘I Want to Walk You Home’ and ‘Walkin' to New Orleans’ like everyone else, but these didn't quite prepare for James Carroll Booker III. Introspection, vulnerability, self-examination and soul-baring emotion are not what you associate with Fats, Little Richard, Lee Dorsey and the rest. What Booker offered was outside my experience of New Orleans music. Sure, he took the piano style of Professor Longhair to new heights of virtuosity, but he offered something else: ‘gumbo’ as a secret source of healing power, perhaps.

Support came from Brett Marvin and the Thunderbolts (two sets from the Thunderbolts; two sets from Booker) but I only had eyes for Booker. He certainly cut a dash, with a star on his eye-patch (he lost an eye through shooting bad heroin, it was said), and a diamond on his front tooth that flashed in the spotlight every time he smiled, or, just as often, grimaced (it was hard to tell which was which). The mystery was how anyone could acquire such musical skill and be so comprehensively, mortally wrecked when either would be a lifetime's accomplishment for lesser mortals. The concert coincided with a sustained acid flashback on the part of the performer, of which we were treated to a running commentary as he played. Innocuous songs took on a new harrowing force. ‘Lonely Avenue’, the Ray Charles tune, was not a boy-loses-girl song, as previously supposed, but was transformed into a graphic trip through cold turkey.

The entire performance was driven by freakish, fantastic anxiety. It was impossible to foretell what the maestro would play or say next. Fats Domino and Dr John tunes were strung together. Or should I say, ‘strung out’ together: addiction was a running theme. ‘Right Place, Wrong Time’ itself became a boogie-woogie rollercoaster ride that communicated elation, danger and panic in lightning succession, with the extreme mood swings that typify junkiedom: “I was in the right place, it must have been the wrong time / I said the right thing / Must have used the wrong lines…" And, in keeping with his confessional tone: “It was the right arm / I must have used the wrong vein.” ‘Junco Partner’, the ultimate doper anthem, was given a hell-bent, demonically gleeful delivery. Dark secrets emerged. It seems he sold ‘So Swell’ to Aretha. The disclosure made perfect sense. ‘So Swell’ has the pay-off line: “You're so swell when you're well / You've just been sick so long.” Vengeful self-loathing was never Aretha's thing, whereas Booker made it his own.

The piano-playing was incomparable. Imagine Professor Longhair raised to the level of Liszt, larded with unlikely motifs and quotations. The Woody Woodpecker theme and Flight of the Bumble Bee surfaced with obsessive regularity. And whole tunes, not just licks, were repeated. ‘Please Send Me Someone To Love’, which equates personal loneliness with nuclear holocaust, received two airings. It was as if Booker had been forewarned that this was his last night on earth. In fact, he finally shuffled off to boogie-woogie heaven six years later, in 1983, at the age of 43.

The spirit of that night is most faithfully captured on The Piano Prince From New Orleans and Blues & Ragtime From New Orleans, two live LPs recorded in Germany on a tour the preceding year. He's sporting an Afro on their respective covers, whereas I remember him as he appeared on the cover of Boogie Woogie & Ragtime Piano Contest, recorded in Zurich on the 27 November 1977, and in the picture that heads this blog, with the distinctive star eye patch, which he's also sporting on the cover of Junco Partner, Island Records, 1976: the definitive studio album, not that I would pass on anything by Booker. James Booker: Manchester 1977, was recorded at Belle Vue Manchester the same week as the 100 Club appearance. The backing musicians, including Norman Beaker and Dave Lunt, contrive to iron out Booker's idiosyncrasies, but it’s a worthy document (on Document Records actually). However, Booker had evidently come down from the acid. And now comes a documentary film, Bayou Maharaja – of which I’ve heard glowing reports. 'Bayou Maharaja' looks set to join all those other titles, like ‘The Piano Prince of New Orleans’, ‘Little Chopin in Living Colour’ and ‘Black Liberace’, which so signally failed to attract attention in his lifetime.

Posted by Mike Butler

on Sunday, 31 July 2016

·

El Niño de Elche has come to Manchester. This, according to De La Puríssima (Eva and I bumped into her in Tampopo last week), because a “visionary” at Instituto Cervantes recommended him (and De La Puríssima) to MJF programmer Steve Mead. This wouldn’t be the person from Instituto Cervantes who introduced the afternoon set by claiming that Elche was in Valencia. (“Alicante! Alicante! Elche is from Alicante,” corrected a voice in the audience from the seat next to mine.)

Presumably in homage to the host city, Darío del Moral, the synth player (he later strapped on a bass), wore a t-shirt sporting Peter Saville’s monochrome art-work for Unknown Pleasures. We can argue about the play of dark and light forces in the music of el Niño de Elche, but there was a sense of occasion that no-one present will soon forget. The concert was both an exemplary exercise in catharsis and a brush with immortality. Most people were expecting the Gypsy Kings.

An ominous drone that builds. Resonating guitar strings. The stocky figure of el Niño, already half sunk in trance, is swaying. Utterly mesmerising, and el Niño has yet to speak. He holds out a poetry book (Porción del Enemigo by Enrique Falcón, as el Niño later told Eva). What follows next is not a straightforward recitation, more like a call to prayer from a muezzin blessed with a golden voice. The hairs involuntarily rise on the back of my neck (Reem Kelani was the last singer to have this effect). Eva leans forward and offers a hasty translation: “Do not let your children play in the gardens of torturers.”

(And now echoes of distant voices. The last words of M: “We should keep a closer watch on our children”; Kevin Coyne’s ‘In Silence’: “Don’t hurt them.”)

It isn’t that el Niño de Elche sings protest songs, it’s more that he’s somehow receptive to the pain generated by evil acts throughout the world, and transmits the intensity and rage through the medium of a powerful voice trained in flamenco. Of course, the transmission of rage is what flamenco has always done, but this is duende on a cosmic scale. And because suffering has no words, so el Niño resorts to shrieks, gasps, moans and, finally, a sustained scream. His body is subject to a paroxysm of jerks, but his hand movements are graceful. This is telling, and somehow symbolic. He has something in common with Phil Minton, the great non-verbal articulator of the visceral, and, as we know, with Ian Curtis, who took the sins of the world on his skinny shoulders.

But perhaps I’m not adequately conveying the charisma and humour of el Niño de Elche. One song, ‘Nadie’. – “Nobody knows me / Nobody has discovered me yet / Not even the artichoke of my shower” (this free translation comes from Eva) – has him chuckling away, taking the audience into his confidence and exposing the psychosis that lurks behind charisma and humour. In short, he’s a consummate actor as well. There was a comic note too, when Raúl Cantizano exchanged his axe for a Spanish guitar (at last, flamenco!) modified by two tiny fans whose whirling blades recreated flamenco’s rapid thrum by mechanical means. The song was ‘Canción de Corro del Niño Palestino’, where suffering quickly outstrips the power of words, and the laughter soon died.

I shall go and live in Madrid if only to hear again the passion and sincerity of el Niño’s performance.

Posted by Mike Butler

on Friday, 29 July 2016

·

Vyamanikal, Manchester Jazz Festival, 28th July, 2016

For the Vyamanikal project, Kit Downes and Tom Challenger decamped to rural Suffolk to explore the acoustic properties of old churches, with Kit Downes extemporising on pipe organ in a reedy sepulchral way, and Challenger responding with a minimal, keening saxophone. Singularly responsive to the spirit of place, the music was unique and full of character, and turned on the peculiarities of oft-neglected, wheezy old instruments.

Extending the concept to historic St Ann’s Church in central Manchester is an interesting idea, though this sacred space is rich and ornate and the church organ is well maintained, with some original pipework from 1730, when it was built. Tantalisingly, Downes mentions that his father learned to play on the very same instrument.

Downes is drawn to the subtleties of timbre and texture and extracts a thin, shifting sound; more misterioso than pomp. It’s music that evolves in a natural organic way, however, and these are just quiet beginnings. Challenger complements with plangent simplicity. A screen just behind the players shows visuals of eerie flat expanses and cornfields, presumably from the same Suffolk wilds. This invites comparison to the old BBC Christmas adaptions of M.R. James ghost stories, but it's all a bit literal: it seems a shame listeners can't be trusted to make the connection for themselves.

Downes temporarily diverts to a small harmonium with very much the same tonal register. We’re told that the music is fully improvised and there is no reason to doubt it, but it seems very purposeful in its meditative way, and the interplay between the two players is confident. It hardly seems necessary to say that the sound is extremely haunting. Applause would only break the spell.

Finally the organ regains some of its conventional power, and events take on a more grand guignol aspect, as if Count Magnus has arisen from the tomb.

No, that’s a rather reductive characterisation (you see how sensational the unfettered imagination can be). Say rather that the music evokes the circle of life and death, and is more gratefully life-affirming than gloomy.

Posted by Mike Butler

on Wednesday, 27 July 2016

·

Tuesday, 26 July, 2016, Royal Northern College of Music

Let’s Get Deluxe is the title of the new album and an unnecessary statement to apply to The Impossible Gentlemen. They can’t help but get deluxe. Unfailing quality is a given. The tune opens the concert – something of MJF veterans, this is their fourth appearance under that banner – and it slips down like a treat: high-calibre jazz funk, effortlessly sustained by guitarist Mike Walker’s joie de vivre. Though capable of emulating the immaculate polish of a Crusaders or Steely Dan indefinitely, the Gentlemen opt for different colours, different moods. The second tune (sorry, I didn’t catch the name) is more cussedly prickly; ‘It Could Have Been a Simple Goodbye’, dedicated to John Taylor, is an opportunity for Walker to wear his heart on his sleeve, always gratifying to behold. The central Impossible partnership is between Walker and the pianist Gwilym Simcock and how the latter’s virtuoso, slightly academic muse has been tempered by Walker’s warmth! The dazzling gaucherie has been laid aside in favour of something that swings, and, though capable of chopping time with the precision of an atomic physicist, he restrains himself from doing so.

‘Dog Time’ starts with Mike in ominous free-form and climaxes with exultant baying, with sinister stalking in-between. There’s a cinematic component to the band as well, offering soundtracks to non-existent movies, with listeners in the role of cinematographer. ‘Dog Time’ is clearly a spaghetti western, with a full cast of desperadoes and badmen.

The addition of Iain Dixon’s saxophones (and occasional keyboards) adds to the expansive sound. He plays with confidence and can vie with Walker for tenderness. Drummer Adam Nussbaum swings the band with considerable power, but his chief asset is to mix unbridled power with delicacy. On ’Speak to Me of Home’ he gauges the intensity with precision. Do we miss Steve Swallow? With respect, we don’t, not when bassist Steve Rody holds the centre with such unruffled authority. He’s a conventional time-keeper of immaculate clarity, but then clarity is the sign of a Gentleman.

‘Barber Blues’, graced by a little fugue between Simcock and Walker, slips into a drum solo by Nussbaum, interrupted by a trick coda that catches some of us out. These guys are playing games with us. ‘Propane Jane’ locks into a solid groove and, again, Mike Walker lights up the night. A true guitar hero, Walker’s trajectory from macho swagger (don’t knock it: swagger is Manchester’s great gift to music) to paragon of warmth and sensitivity is one of the great jazz stories. ‘Clockmaker’, reserved for the encore (and written for Iain Dixon’s dad, Walker reminds us) is something of a Greatest Hit, and an eloquent expression of joy.

In a word, perfection.

Posted by Mike Butler

on Tuesday, 19 July 2016

·

Whest Records WrL-3010

www.zoekyoti.com

Technically, Wishbone is Zoe Kyoti’s solo debut, but there’s a familiarity about the songs, an aroma of Greatest Hits, which can be explained by the fact that some are much-loved in stripped-down versions by Zoe’s occasional string band, The Magic Beans. ’Monsoon’, with two previous incarnations – on The Magic Beans’ debut and Matt Owens’ album, The Aviator’s Ball – has achieved the status of a classic by now. Here powerful nature becomes a metaphor for the necessity of letting go to achieve selfhood, at whatever destructive cost. An ecstatic hymn to bliss, and deeper than anyone suspected, ‘Monsoon’ opened the floodgates to Zoe’s creativity. All the songs on Wishbone are self-penned or co-writes, and constitute a defining statement of the Kyoti aesthetic.

She has a very feminine capacity for finding fresh personalities to inhabit with every song. The title track blends sensuality and restlessness in a very winning way. ‘Don’t Spend Your Love On Me’ comes close to uncovering the scam on which mass entertainment is based (it’s as if Dusty Springfield admitted she didn’t only want to be with you).

In ’My Evil Soul’ Zoe play-acts the femme fatale with great gusto (to sweet Hot Club guitar licks from Uli Elbracht), but the demons are real on ’Old Rope’. Zoe loses all inhibitions in this especially sombre song, relieved only by a neo-psychedelic chorus. When it all gets too dark, she can always return to unabashed beauty, of which ‘No Way Back’ and ’Anything You Can Dream’ are prime examples.

But it seems that prettiness is no longer enough for Zoe Kyoti. Seductive charm comes easily, and her ability to enchant and beguile is a given. Yet Wishbone is interesting for the way the desire to please co-exists with hints of depravity and malice and just enough dark side to exude a heady sense of danger. This of course, makes Zoe more attractive than ever, and so we come full circle.

Posted by Mike Butler

on Tuesday, 14 June 2016

·

Alan Butler – 82 today! – recalls D-Day, when soldiers camped in the front garden of 14 London Road, and the woods became a military zone…

from the collection of A.H. Butler

We had Italian Prisoners of War in the area where I was. Where they were billeted, I don’t know. They weren’t billeted in the village, but they used to turn up on a lorry, and then go off to the different farms where they were allocated. We never saw any German Prisoners of War.

Tanks at Horndean

It could have been a month or six weeks before D-Day that the troops arrived. Several times they were moved on and then you found them at another part of the village. They got them to pack all their gear and depart and ride around and come back.

Some soldiers were actually billeted with us. They had their tent in the front garden of 14 London Road (I suppose it was about 18 foot square). They’d put a big tarpaulin up, or several tarpaulins up, and would sleep under these tarpaulins in their sleeping bags in a big makeshift tent.

There was only one time when they slept in the house, when a sudden shower came on, and the sides of the tarpaulin were rolled up for headroom, and all their bedding got wet, or some of them. So my mother said they could sleep in the house.

My dad was a policeman and when he finished his shift, in the early hours of the morning, he couldn’t get into the house, because there were soldiers asleep on all the chairs and settees, on the staircase, and some were sleeping on the dining room table, and some under the dining room table. The house was full of soldiers. They didn’t go upstairs (they might have gone upstairs to use the toilet), and we boys and my mother – my grandmother was there at that time – had our own bedrooms. My dad came in, found out he couldn’t get upstairs to use the bathroom or go to bed, so he went back to the police station, which was only two doors away, and had a little kip there, until all the soldiers departed.

My grandmother Mary Harcourt did her bit for the war effort, so my father said, by teaching the British army how to play Mahjongg. I’ve known my grandmother at the table with three soldiers, and, because only four can play at a time, other soldiers were sitting on chairs there waiting for their turn to have a game of Mahjongg.

14 London Road was a open house for soldiers, and Cowplain generally was very soldier-friendly. Some families adopted some of the soldiers. My second cousin, Joan, married one of the soldiers, Bill Starkey. He was in the woods, The Queen’s Inclosure, and because he was good at football, he had to be got out, so he could play football for the army football team. He had to be found a job. What his job was in the woods, I don’t know. They knew all the plans, more than likely, for when D-Day was going to happen in there.

So Bill came out, and the only job they could think for him was as a military policeman, so they gave him the job of making some village roads one-way. My second cousin Joan was driving her father’s grocer’s van, and objected to being stopped by Bill and told she couldn’t go down this road. From these inauspicious beginnings they started a relationship, and during the war, when Bill was still in the army, he came home on leave and they got married. It was rather a rush wedding. My mother gave one jar of cherished preserve fruit in a kilner jar to help with the wedding breakfast. He survived the war and eventually lived next door to my parents. He finished up his playing years with the Cowplain football team.

from the collection of A.H. Butler

My mother charged accumulators. Accumulators were the power behind batteries for wirelesses, and they had to be charged up nearly once a week. An officer would come along to my mother and have his solid pack accumulators charged up for his wireless. My mother was horrified one day when he turned up at the side door of 14 London Road (there were three doors to 14 London Road) escorted by two military policemen. My mother thought that he was in trouble. But he wasn’t. He simply had to come out of the woods, which was a secure area, to collect the battery. The policemen were to make sure he didn’t talk to anybody about what was happening in the woods. Normally he collected a battery and left one, but this time he didn’t leave any.

from the collection of A.H. Butler

Just before D-Day the soldiers were all issued with French currency, and my mother was given two of these franc notes, which I have in my collection. And then, at Christmas, some soldiers sent my mother Christmas cards, which I’ve got in my collection too. One reads “To Reggie, Michael and Alan,” that is, the children in the household, “with best wishes, John”. And this from the 20th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery: “To our good friends of Cowplain, with every good wish for Christmas and the New Year from the Gunners of Spring, 1944.” That phrase, “the Gunners of Spring”, suggests that soldiers were in Cowplain earlier than I thought: if D-Day was in June, they must have been in the village at the back end of spring.

from the collection of A.H. Butler

That’s how much they thought of us. A couple of things were always in short supply at our house: sugar (we went through an awful lot of sugar), and tea too was very scarce. The soldiers gave my mother either one or two big bags of tea. The tea they were issued with didn’t come in packets, they were in small bags, about nine inches square, and it was full of tea, with a draw cord at the top, to keep it fresh. My mother was given two of these bags as a parting gift. Whether they gave her any other food out of their supply, I don’t know, but I’ll always remember the tea.

My mother would let the soldiers use the bath. Because they had none or very basic washing facilities, a cold shower perhaps, she let them have use of the bath. And one day a lieutenant came to the door, a complete stranger, and said to my mother, “I understand that this is the house that I can have a bath at.” And my mother said yes. And so he left her sixpence to pay for his bath. The soldiers she didn’t charge at all, but she took the sixpence from the lieutenant.

from http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/war/evacuation.htm

Cowplain took evacuees from London and Portsmouth. I can remember an endless stream of cars and wheelbarrows coming out of Portsmouth one evening, when I was a child. Halls and churches put them up. They would accommodate them until they found somewhere to live.

Huts were built in some spare ground in Hart Plain Avenue (where Hart Plain Avenue joined Silvester Road) for more evacuees, but the evacuees never came. They stayed empty for a long time, and then it was decided to turn these wooden huts into a junior school, because we had no junior school in the village, and when the war started, it was overwhelmed by children.

I’d been moved to the senior school. In Cowplain you had a huge great senior school that had a catchment area of Waterlooville, Purbrook, Denmead, Widley and went as far as Rowland’s Castle but didn’t include Havant. It was a funny old radius actually: it went to the top of Portsdown Hill. And then the other way it went to Denmead, Hambledon, Horndean, Clanfield, Lovedean. At one time it was mixed, but then they divided it so you had girls in one half, and boys in the other half. Separate provision was made for the girls and boys. There was no contact with girls that I can remember.

When there was an air-raid, we, the juniors, went up to the shelters. And it was a good old walk to get to the air-raid shelters from the school, about 200 hundred yards, and we were allocated the first one, because we couldn’t walk very fast. We were only little tots. And the senior boys went to the classrooms we had just vacated and trusted to the blast walls to protect them. Luckily, it only ever happened once as far as I can remember. We had dummy runs, but there was actually only once we had an air-raid and were evacuated to the shelters.

So there was one air-raid when we were all summoned there, and the other ones were dummy runs. And you had to put your gas mask on, and they were the most unpleasant things going, because they would steam up in no time at all. I would hate to have to wear one in a gas attack. Any rate, it never happened, thank goodness.

These wooden huts, as I say, had been built, and never used, and then, as I say, it was decided to turn them into a junior school. And so about 1942 (yeah, it would have been about 1942), we were moved from the senior school over into the huts. They were terrible. All you had was a big stove in the middle, and it was the job of somebody in the class (there was big buckets of coal there: I think it was coal, it might have been anthracite) to keep these stoves topped up in the winter. And the classrooms were still cold even with the stoves on. We had to wear our coats in class, they were that cold. Because the stoves radiated a little bit of heat, and beyond that, nothing.

I think there are four or five junior schools in that village now. I wouldn’t like to say.

This map shows our house – the red is 14 London Road (that’s the length of our garden) – and the territory the army took over.

Have you got the photograph I took of the bombs? The drawing pins are the bombs we had. One landed on a poultry farm and killed hundreds of chickens, and the other was at the top of Park Lane. See that square building there? That was one of the old tram sheds. Fodens had it – I didn’t know this until recently virtually – and they were storing torpedoes in there, for submarines. Perhaps I didn’t notice them come, or perhaps they all travelled at nighttime, I don’t know, but somebody knew about them, and the Luftwaffe tried to bomb it, and they were just that little bit out: they bombed the other side of the road (the corner of Park Lane), the bottom of our road and a field. We were lucky. They were the only bombs we had in Cowplain.

As I say, the soldiers were often on the move, and the HQ, we found out afterwards, was Southwick House, which was five miles by road. It’s a museum now, with the layout for D-Day.

Of course, D-Day was cancelled at the last minute, because the weather was that bad. The weather was blowing a storm and it was just impossible, so D-Day was put back a day to the 6th of June. The weather people were involved for a long time to predict a good day for the invasion, but they got it completely wrong. Meteorology then was not the advanced art it is today.

So they all departed. The village was quite empty of tanks, vehicles and guns. We did have some tanks: there were a lot of Bren Gun Carriers (you had a trailer behind the Bren Gun Carrier, and then a small field gun towing behind the trailer). And they all departed. What made my parents’ property quite attractive, was the very wide piece of grass from the edge of the road to the fence of the house (at one time the Horndean Light Railway tram ran along there), and so they army was able to park their vehicles well off the road. Now it was empty.

It was the evening of the 5th of June and suddenly there were aeroplanes in the sky. We looked up, and there were Airspeed Oxfords (they were mainly Oxfords) towing Horsa gliders. They went over the house and we had a good view from the back of the house because the ground dropped a bit. The woods were three quarters of a mile away, and visibility ceased after the woods. But you can imagine, the sky was full of planes. As far as we could see to our right, and as far as we could see to our left, the whole sky was full of aeroplanes and gliders, spaced quite apart but limitless. That’s when we realised that some action was going to take place.

This was getting dusk, at ten o’clock or eleven o’clock at night, so it wouldn’t be long before it would be dark, and then they would fly across the Channel into France, and the planes would shed their gliders, and the gliders would land with the airborne troops inside them.

Mind you, that happened again several weeks later. They wanted to secure a bridge in Holland. They didn’t succeed actually. They couldn’t secure it and the Germans took the bridge, but they did their best, and again the sky was full of Oxfords and Horsa gliders.

Further reading: http://www.portsmouth.co.uk/news/defence/horndean-s-wartime-past-1-6573671 – source of Tanks in Horndean and Home Guard pictures.

Coming soon: Bicycle Ride to Love

Posted by Mike Butler

on Friday, 10 June 2016

·

A ringing bell signals the start.

Eddie Little: Manchester Jazz Society, 8th of June, 2016...

Mike White (from the floor): 9th of June.

Eddie: I beg your pardon. 9th June. And this evening it’s Mike Butler, talking about Michael Garrick, Mike Westbrook, and a deep English jazz.

I chose the subject mainly because I wanted to share a great interview Michael Garrick gave me in March 2006. And it seemed natural to couple him with Mike Westbrook, who I also interviewed, circa October 1998, but the transcript of that interview is lost – one day all the contents of my floppy disc vanished.

Off: Oh!

It happens. So I have a hard copy of the finished piece, but it seems fairly run of the mill stuff. So there’s going to a bit more direct quotation from Michael Garrick than Mike Westbrook tonight.

Perhaps the fact that one is a Michael and the other is a Mike is significant. The rule is, the younger you are, the more formal your moniker, and then, as you mature, you earn a certain chummy informality. It takes determination to hold onto Michael, as I know, and implies a certain hankering after respectability. Mikes however are… Well, Mikes go with the flow. And I think you can hear the difference in the music.

Michael Garrick

Mike Westbrook

Mike Westbrook

Both men are pianists, composers, arrangers and band leaders associated with what we retrospectively know as Jazz Britannia. Michael Garrick was born in Enfield, on the 30th May 1933, and Mike Westbrook was born in High Wycombe on the 21st March, 1936. Only three years separate them, although Garrick seems much the senior figure. Jazz Britannia, a term coined by the BBC, is apt, because both in their own way brought an English sensibility to jazz, which up to then was thought largely to be a North American activity.

‘Deep English’? Well Englishness is problematic, as I hope to show. But before I attempt to disentangle the English stain, it might be best to start with the much more uncomplicated North American influence. Duke Ellington was the household god of Garrick and Westbrook, as he was to every musician who aspired to make jazz a serious art-form. And what of tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, a staple of the Duke Ellington band between 1940 and 1943? My first selection is ‘Webster’s Mood’ by the Michael Garrick Septet. Joe Harriott and Tony Coe take the solos….

‘Webster’s Mood’ (Garrick)… 6.52

Here’s what Michael Garrick told me about it.

“I wrote that the day after I heard Ben Webster live, in London. I’d heard a record of him, with Oscar Peterson, but then when you encounter the real thing, it’s quite different. So I used to practise the piano in a rehearsal studio in Oxford Circus. I just went in as usual – you pay whatever it was; it was about 2/6 for an hour, I think – and just began playing that tune. You play the first phrase (“What’s this?”) and follow it. Then I realised I had a blues. But it was a blues with different changes. It had minor chords in the middle which a normal blues doesn’t have. And the whole movement of it, with that majestic, stately, slowish sureness about it. And I thought, this is from Ben Webster.”

The line-up is Michael Garrick, piano, Ian Carr, trumpet, Don Rendell, saxophone, Dave Green on bass and Trevor Tomkins, drums. As I mentioned, the soloists are Joe Harriott on alto saxophone and Tony Coe on tenor saxophone. It comes from the LP Black Marigolds, and was recorded in January or February, 1966.

It’s as much a tribute to Joe Harriott now, as it is to Ben Webster, I say. Garrick: “Yes, that’s true. Although lots of people have played it. Don Rendell was on that session but he didn’t solo on that particular piece because you were constrained by time. You don’t want the track to go on forever. Which is a great shame. Because on gigs – we did gig that sextet – everybody would solo on it, but then the piece would last a quarter of an hour. And in those days, on LPs, that would have filled almost one side. The producer would say, “It would be better if that one was shorter.” And of course, it is different too, when you’re live with people living and breathing in front of you, as long as they’re being interesting then it doesn’t matter if they go on for ages. But when you’re listening at home and you put a CD on, it’s quite different. You need conciseness.”

Second track, Mike Westbrook’s take on Lionel Hampton’s ‘Flying Home’, which is crowded with incident. John Surman leads on baritone sax…

‘Flying Home’ (Westbrook)… 4:20

A shot of the Concert Band circa '67, with (l to r), Harry Miller, Mike Osborne, John Surman

Mike White: What year is that?

1969, I think.

If Mike Westbrook spent the rest of his career avoiding jazz cliches, it’s because he used them all up on ‘Flying Home’. [Profound silence. Mike: “Oh oh!” Eddie and Eva dutifully laugh.] It comes from Release, a 1969 album by The Mike Westbrook Concert Band on Deram. After John Surman, Malcolm Griffiths takes the trombone solo and Nisar Ahmed, otherwise George, Khan is getting all hysterical attempting to channel the spirit of Coleman Hawkins. Alan Jackson is the unruly drummer.

And here is Michael Garrick’s tribute to …. Well, you can probably guess who. The title is ‘Mrs Marietta Clinkscales’, which is a clue when you know that Mrs Marietta Clinkscales operated as a piano teacher in the Washington D.C. area in the early decades of the 20th century.

‘Mrs Marietta Clinkscales’ (Garrick)… 7:31

‘Mrs Marietta Clinkscales’ comes from Michael Garrick’s ‘A Life of Duke’, commissioned for the 20th International Ellington Conference in London, May 2008. Were you there, Peter?

Peter Caswell: Yeah. And Delia.

A Shakespearian cadence was added to the album release on Jazz Academy, Garrick’s own label: Lady of the Aurian Wood, subtitled ‘A Magic Life of Duke’. The singer is Norma Winstone. The phrase she quotes, “Don’t do that, Henry”, is, of course, culturally specific, despite the USA accent elsewhere. “Don’t do that, Henry”, I needn’t explain, is the running refrain of the celebrated monologue with Joyce Grenfell as the nursery school teacher. Just what Henry is doing is never specified.

Likewise, Ellington tributes are sprinkled through Westbrook’s career. Notably, On Duke’s Birthday, written to mark the tenth anniversary of Ellington’s death in 1974, and possibly a more meticulous, mature reworking of an early jazz inspiration than ‘Flying Home’. It’s not included here because of time limitations and because I don’t have the CD.

Instead let’s pursue the English theme. The third edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD has this to say in the Westbrook entry: “Westbrook belongs to a long-standing English musical tradition one associates (though Westbrook is from semi-rural High Wycombe) with the Lancashire Catholic background out of which John Lennon emerged (and to which novelist/composer Anthony Burgess has paid tribute)…” Now while you’re thinking about that, and if anyone can tell me what it means I’d be grateful, the next selection is ‘Waltz (for Joanna)’ from the 1969 double album, Marching Song by the Mike Westbrook Concert Band.

‘Waltz’ (Westbrook)… 5:51

Marching Song is a suite on the theme of World War 1 – Westbrook served his national service in Germany in the early fifties when whole swathes of the country were bomb sites – and ‘Waltz’ is a pretty interlude amid the angry turbulence elsewhere, but listening to it then, I think a bit of the turbulence does creep in. Tommy is in the trenches thinking of his sweetheart back home. It’s an early vehicle for John Surman’s lyrical soprano sax. Sometimes the arrangements recall Gil Evans, but Marching Song, I think, is jazz with a very English identity, about a national cataclysm.

Garrick again: “Right from the earliest times, when I was still in college in the fifties, it struck me that jazz was obviously the next step forward in serious music. Because it engages in time. Time and pulse and swing. That element, which so far, in so-called classical music, just didn’t exist. That was the new thing – the freedom in relation to time, which didn’t exist before. And so therefore it seemed to me then, this is a completely new way of taking music forward. So I thought people should be educated in it. That’s been my stance ever since.”

It might be significant that neither man has a formal music education. Westbrook studied art at Plymouth College of Art, whereas Garrick studied English at London University. And Shake Keane, who played trumpet in Garrick’s group, also studied English at London University. “You see Shake Keane was a poet, and he came to England later than Joe Harriott. They didn’t know each other, because he came from St Vincent. He came here to study English at University College, London, which is where I was. I was unaware of him then, although we were at the same college. He didn’t put in much time there, and in the end he pulled out, after his second year…

“So when we did meet, which was at the Marquee Club, Wardour Street, where my quartet and his quintet played opposite each other every week, Saturday night, 1958-59… At the same time I was asked to do this Poetry and Jazz thing, and I had a quartet, which went down to a trio, that’s right. We had a trio and I said, ‘Shake, would you like to play with us at this Poetry and Jazz thing with Spike Milligan and Laurie Lee and Dannie Abse?’ And so he played with us, and he was totally sympathetic to the idea of poetry and jazz, being a writer himself.” [‘Shake’, incidentally, is short for Shakespeare; his other name is Ellsworth.]

It’s poignant to think that 400 people had to be turned away from the first Poetry and Jazz In Concert event at Hampstead Town Hall on February 4th, 1961. The success led to a follow-up at the Royal Festival Hall and then to a concert at Belgrade Theatre, Coventry, which marked the debut of the Michael Garrick Trio with Shake Keane. Dates at Cheltenham, Birmingham and Oxford followed, and the Michael Garrick Trio expanded into the Michael Garrick Quintet, with Shake Keane and Joe Harriott as full members. They participated in Centre 42 events. Centre 42, er, was an attempt by the Trades Union Congress to devolve culture and art into the regions, with the playwright Arnold Wesker as a guiding force. It was crucial to the development of the folk music revival, but that’s by the by. Poetry and Jazz In Concert spawned more than 250 concerts, two LPs on the Argo label, and a poetry book, which you can pass around. [Produces Poems From Poetry & Jazz In Concert, edit. Jeremy Robson, 1969, Panther.]

Jeremy Robson

“The opportunities came. I didn’t invent them. They came along. I thought, oh, this is great. It’s what I’d like to do. Poetry and Jazz for example. A poet called Jeremy Robson was organising poetry and jazz together in the beginning of the sixties and he heard us, and said would I like to work with him? Because he was going to expand and work with other poets. That’s how it happened. Through that came the first Argo recording which has just been reissued, Poetry & Jazz In Concert.”

The Argo records are weighted more to poetry than jazz and only Adrian Mitchell on the first record and Jeremy Robson on the second actually attempt to read to jazz accompaniment. But the jazz and poetry are integral elements, with the jazz as a direct response to the poems. ‘Wedding Hymn’, the next piece we shall hear, was inspired by Dannie Abse’s ‘Epithalamion’ (a tough word to pronounce), a poem for his wife, Joan Abse. Here’s a flavour:

Singing, today I married my white girl,

beautiful in a barley field.

Green on thy finger a grass blade curled.

So with this ring I thee wed,

and send our love to the loveless world

of all the living and all the dead.

’Wedding Hymn’ (Garrick Quintet)… 8:07

The line-up is Joe Harriott, alto sax; Coleridge Goode, bass; Colin Barnes, drums; Shake Keane, flugelhorn; Michael Garrick, piano.

Garrick on Joe Harriott: “Joe Harriott was a Charlie Parker man through and through. He’d been brought up in an orphanage in Jamaica, the Alpha Boys’ School.”

I chip in, “Oh, the one that gave birth to The Ska-talites?”

“That’s right, and not a few others. And they must have been very good teachers there, because he started on clarinet. But when he arrived here, which was in 1951, although I didn’t know him till seven years on… Everyone says he arrived here and he was playing fantastic on arrival. So where he got that from is a mystery. In a home for wayward boys or orphans, accumulating all that knowledge and putting it onto his horn, all the Charlie Parker compositions, for example, just bore him along. That’s the mystery of Joe Harriott.

“And there was this idea about free form. It was then that the Caribbean influence came into his music more. There’s one in particular called ‘Calypso Sketches’. It’s a deliberate calypso thing. [As ‘Calypso’, it appears on Free Form by the Joe Harriott Quintet, Jazzland, JLP49, 1961.] But the other one,” [Abstract by The Joe Harriott Quintet, Columbia 33SX 1477, 1962] “it’s more like a cross between circus music, European impressionism and bebop. They’re wonderful things, the Joe Harriott free form records.”

So how calypso is ‘Calypso Sketches’? In 2004 the Michael Garrick Jazz Orchestra issued a tribute album called Big Band Harriott, so let’s find out.

’Calypso Sketches’ (Garrick)… 4:51

From the sleeve-notes: “To the fore, Martin Hathaway and Quentin Collins (trumpet), Jimmy Adams (trombone) and Gabriel Garrick (trumpet). It’s 2.30am and carnival time. You could say that this one is closest to Joe’s Jamaican roots, but his gaze was always onward and outward.”

More Garrick and Westbrook after the break, shall we say? Thanks guys,

[applause]

* *

OK, to pick up where I left off, and without further ado, so Michael Garrick said: “So Poetry and Jazz got me on that tack, and it also helped my composing immensely, because I found that by taking a poem – not any poem, of course, because you can’t set Shakespeare’s tragedies to jazz too easily – but a lyrical poem, it doesn’t matter whether it’s modern or an ancient ballad, it will give you the mood, it will give you the movement. So you can write music out of the feelings you get from it. That’s how I found I could write original music. I wasn’t thinking, now I’m going a write a blues, or an ‘I’ve Got Rhythm’ type tune. I just look at the poem and let the music come out of it. And so it would lead to different shapes of composition, according to the poem – odd numbers of bars. Most jazz music is written in 8-bar phrases. Instead of adding up to 16 or 32 bars, I might suddenly find I’d got a piece with 19 bars or 21. But then which held together because the starting point in itself held together. And then I found I could do it without poems. Still things would come out odd shapes and so on.”

I said that Englishness is problematic. I said that ‘Webster’s Mood’ is so sublime that, for me, it could go on forever. In fact, whenever I do play it, I have to speedily get up to raise the arm before the next track starts. And if I’m a bit slow, this is what comes on.

’Jazz for Five’ excerpt (Garrick)… 1:23

[John Smith recites to Garrick’s piano:

You are winter

You are a landscape of snow…

And though my arms are not yet ready to hold you

Because of the loosened tenderness of your especial being

I will let the air only vibrate with a small celebration of words

Saying

I love you

You are winter

]

Now can anyone defend that to me?

Eva: Yeah, yeah. [Chuckles elsewhere]

Don Lee: Mike, who was that speaking?

It’s a poet called John Smith, it’s called ‘Jazz For Five’, and what happens next is a series of duets between John Smith, the poet, and the different musicians. I don’t think it’s as good a poem as the Dannie Abse. I don’t believe it. It’s pitched in such ludicrously overblown terms. But I think a bigger stumbling block might be John Smith’s voice.

[Murmurs of agreement]

That awful received pronunciation, which was standard in 1966, but which everybody has thankfully dropped since.

[Titter from Eva. She tells me that there was conversation during the break about my accent.]

All the poets on Poetry and Jazz In Concert possess it to some degree, though none have it as bad as John Smith.

So this is what Garrick had to say about John Smith: [posh, high-pitched voice]: “He has a very interesting voice.

[Mild laughter]

He speaks like that. He lives in South Africa, Cape Town. [Resumes normal voice] And he doesn’t intend to come back. But despite his voice, he was a great character. And he wrote a cantata for us as well, called Mr Smith’s Apocalypse. Although that’s for a choir and organ, and Norma Winstone, and a sextet of musicians. It hasn’t got an orchestra.”

And I chip in. I say, “I did hear it one time, and I found it a bit heavy going actually.”

“Oh it is. It’s very heavy going, I promise you. But then again I thought what he was trying to say was something that should be said. You call to God for help when you really need help and where is he? Gone on holiday. So the only answer is, if you want something like a god, you’ve got to look for him in a human being. You won’t find him anywhere else. That was the theme of it. It was good fun though. I know it’s heavy going. And the words were so dense, that there was very little room for jazz improvisation. But we did get some in. It’s always a compromise, you know.”

The Englishness is problematic, because, England being England, a class element always comes into it, of which received pronunciation is the most obvious outward sign. Duke Ellington is alright, but on the UK side, Garrick’s music (and Westbrook’s) are nurtured by secret wellsprings, and these sub-streams are things like art song, George Butterworth, Vaughan Williams and Constant Lambert setting the poems of Li-Po. [Constant Lambert and Li-Po are the antecedent of the Garrick album, The Heart is a Lotus, except that Garrick fills the roles of both Li-Po and Constant Lambert, as lyricist and composer, which is impressive.] Another piece, I think, before we plumb these murky depths further. This is ‘Rustat’s Gravesong’.

[Bass and John Smith speaks… “A blue dusk girl…”]

Oh, sorry guys, we’re getting more John Smith there. It does sound better, doesn’t it? But, OK, I’ll put on ‘Rustat’s Gravesong’.

‘Rustat’s Gravesong’ (Garrick)… 5:14

Yeah, ’Rustat’s Gravesong’ was recorded in a concert with a jazz group and choir at St Paul’s Cathedral in 1968. Providentially, a French TV crew were present, and the short film they made can be found on Youtube. I mailed the clip to selected Society members earlier in the week. But the event was captured on record. A stereo tape machine was found from somewhere and a single microphone was suspended across the chancel directly above the players. The sound is excellent for such primitive resources, and captures well the rarefied atmosphere. The saxophonist is Jim Philip, and I think the sacred dabblings of Jan Garbarek have an earlier precedent in his swirling, plangent tone. “Jazz Praises is an English experience, retelling the American jazz dream in an Anglican setting.” It works because of a refreshing lack of piety, I think. The jazz group, on the evidence of ‘Rustat’s Gravesong’, don’t rein in the ferocity.

To be an artist in England is to be an outsider, but then artists are always outsiders. There’s always this tension in Garrick's work between rebellion and respectability. His tireless work to get jazz accepted on the curriculum of music colleges is entirely creditable, I think. This comes from a letter he wrote in 1989 to the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music: “The classic sources are clear enough by now: Ellington, Armstrong and Parker, to establish a basic triumvirate. And although primarily an American phenomenon, Britain, placed uniquely between the United States and Europe, has produced much that is original and refreshingly different.”

Westbrook, who shares a tradition and an idiom with Garrick, is by far the more anarchic figure. His idol is not Shakespeare but William Blake, the visionary artist whose phantom arises in every radical period of history, and who had a hey-day in the sixties. Shakespeare has been co-opted by the establishment, but William Blake never could. This is a Westbrook setting of a Blake song, and incorporates a Blake poem.

‘Let the Slave’ incorporating ‘The Price of Experience’ (Westbrook)… 11:28

[Off: Phew!]

‘Let the Slave’ incorporating ‘The Price of Experience’. It comes from a Westbrook album called Glad Day and it was Chris Biscoe playing the passionate alto sax, and Westbrook himself reciting ‘The Price of Experience’. And the stentorian lead vocal, declaiming the song, was my introduction to Phil Minton, who, in my mind, knowing him only from Westbrook performances, represented an English ideal. I pictured a big, bearded Old Testament prophet type. And after all, Minton is only one consonant removed from Milton.

Does anyone know Phil Minton?

Bruce Robinson: I know of him only as a sort of free improvising vocalist.

MB: A free improviser is what he is primarily. I think the Westbrook thing is a sideline, and you get a completely different thing with his free jazz gigs. He’s the pioneer of an extreme kind of body music. He plays alongside hardcore free jazz musicians and proceeds to shriek, burp, gasp, moan, whine, hiss, belch, squall, hoot, snort, coo and choke. And sit tight, I’ve got an example here.

[Anticipatory chuckle from Chris Lee and general laughter]

‘Spermin Spunk About’ (Minton)… 1:48

That was ‘Spermin Spunk About’ by the Phil Minton Quartet from Mouthfull of Ecstasy, free settings of Finnegans Wake.

Phil Minton

In England we judge a person by their accent every time they speak or sing. I did it myself with John Smith earlier. It must be said that Phil Minton’s way out of this particular trap is radical and extremely effective.

Now can I hold up, as an exemplar of everything good about British jazz, a track from Garrick’s 1970 album, The Heart is a Lotus called ‘Torrent’? Which I think finds British jazz musicians finally shaking off their inferiority complex and emerging from the shadows of North American jazz.

‘Torrent’ (Garrick)… 3.44

That was Art Themen and Don Rendell sparring on tenor sax and bassist Dave Green and drummer Trevor Tomkins. Says Garrick (back to my interview): “I was really trying to find a way whereby one could take and draw on the energy and – what else? – sheer creativity that came from America, through Ellington, Parker, Louis Armstrong, that great ebullience, that great life force, that together with this other, English landscape, English poetry and so on, which gives another view of the world. I just thought this contrast in itself gives you the creative edge. So, wilfully or not, I’ve gone down that path.”

As for a sense of English landscape, I would have liked to have played ‘Erme Estuary’ from Mike Westbrook’s magisterial The Cortege, but unfortunately I couldn’t track down a CD copy in time. Chris Biscoe, in a separate interview, told me that The Cortege was the best record he’d ever played on.

And talking about a sense of place, here’s an unexpected encounter between Michael Garrick and Jaco Pastorius: –

“I met him in Boston in 1975…”

Voice off: Jaco?

Yeah, this is Garrick talking. “And when he came here in 1975, he came up here to my house in Berkhamsted, and I took him for a ride round the little villages in Hertfordshire, and he was totally knocked out by it. Because he was born in Florida, and the landscape is still a desert there. When I went to the States myself, only the northern bit, on a long train journey, looking out the window, the difference seemed to me – in England you have countryside; America hasn’t those aeons of cultivation that has happened here. And there again it points up a difference. There’s a rawness to that side as opposed to this. This is 1975, by the way, I haven’t been there since (although I am due to go there with my big band at the end of April to play in New York). It struck me then – England is the granddad and America is the tearaway teenager.”

Mike and Kate Westbrook

Now I love Mike Westbrook because he is or was a loyal employer to some of my favourite British musicians. I say ‘was’ because some of my favourite British musicians are dead or retired – Phil Minton, drummer Tony Marsh, saxophonist Chris Biscoe, and I might add guitarist Brian Godding. A change came in Mike Westbrook’s work around the time he met Kate, soon to be his second wife. She introduced a heady element of cabaret and, reflecting her background in experimental theatre, would create a distinct persona for separate performances. And the Westbrook vision expanded outwards, so that a late masterwork like London Bridge is Broken Down, described as A Composition for Voice, Jazz Orchestra and Chamber Orchestra, has sections called’London Bridge’, Wenceslas Square’, ‘Berlin Wall’, ‘Vienna’ and ‘Picardie’ and sets texts by Rene Arcos, Wilhelm Busch, Andrea Chedid, Goethe and Siegfried Sassoon, some in translations by Kate Westbrook. It attempts nothing less than a survey of Europe and its history over the past hundred or so years.

If you’ll forgive a glib observation, I think Michael Garrick would probably be a Brexit man, and Mike Westbrook would be for Remain. And I’ll close with ‘Picardie Six’ which comes from London Bridge.

‘Picardie Six’ (Westbrook) … 6:25

Michael Garrick died on 11 November 2011, after being admitted to hospital with heart problems. Mike Westbrook is alive and well and still composing, as far as I know. Thank you.

[Applause]

Mike and Don Lee talk 'Incredibly Strange Music'.