Posted by Mike Butler

on Tuesday, 14 June 2016

·

Alan Butler – 82 today! – recalls D-Day, when soldiers camped in the front garden of 14 London Road, and the woods became a military zone…

from the collection of A.H. Butler

We had Italian Prisoners of War in the area where I was. Where they were billeted, I don’t know. They weren’t billeted in the village, but they used to turn up on a lorry, and then go off to the different farms where they were allocated. We never saw any German Prisoners of War.

Tanks at Horndean

It could have been a month or six weeks before D-Day that the troops arrived. Several times they were moved on and then you found them at another part of the village. They got them to pack all their gear and depart and ride around and come back.

Some soldiers were actually billeted with us. They had their tent in the front garden of 14 London Road (I suppose it was about 18 foot square). They’d put a big tarpaulin up, or several tarpaulins up, and would sleep under these tarpaulins in their sleeping bags in a big makeshift tent.

There was only one time when they slept in the house, when a sudden shower came on, and the sides of the tarpaulin were rolled up for headroom, and all their bedding got wet, or some of them. So my mother said they could sleep in the house.

My dad was a policeman and when he finished his shift, in the early hours of the morning, he couldn’t get into the house, because there were soldiers asleep on all the chairs and settees, on the staircase, and some were sleeping on the dining room table, and some under the dining room table. The house was full of soldiers. They didn’t go upstairs (they might have gone upstairs to use the toilet), and we boys and my mother – my grandmother was there at that time – had our own bedrooms. My dad came in, found out he couldn’t get upstairs to use the bathroom or go to bed, so he went back to the police station, which was only two doors away, and had a little kip there, until all the soldiers departed.

My grandmother Mary Harcourt did her bit for the war effort, so my father said, by teaching the British army how to play Mahjong. I’ve known my grandmother at the table with three soldiers, and, because only four can play at a time, other soldiers were sitting on chairs there waiting for their turn to have a game of Mahjong.

14 London Road was a open house for soldiers, and Cowplain generally was very soldier-friendly. Some families adopted some of the soldiers. My second cousin, Joan, married one of the soldiers, Bill Starkey. He was in the woods, The Queen’s Inclosure, and because he was good at football, he had to be got out, so he could play football for the army football team. He had to be found a job. What his job was in the woods, I don’t know. They knew all the plans, more than likely, for when D-Day was going to happen in there.

So Bill came out, and the only job they could think for him was as a military policeman, so they gave him the job of making some village roads one-way. My second cousin Joan was driving her father’s grocer’s van, and objected to being stopped by Bill and told she couldn’t go down this road. From these inauspicious beginnings they started a relationship, and during the war, when Bill was still in the army, he came home on leave and they got married. It was rather a rush wedding. My mother gave one jar of cherished preserve fruit in a kilner jar to help with the wedding breakfast. He survived the war and eventually lived next door to my parents. He finished up his playing years with the Cowplain football team.

from the collection of A.H. Butler

My mother charged accumulators. Accumulators were the power behind batteries for wirelesses, and they had to be charged up nearly once a week. An officer would come along to my mother and have his solid pack accumulators charged up for his wireless. My mother was horrified one day when he turned up at the side door of 14 London Road (there were three doors to 14 London Road) escorted by two military policemen. My mother thought that he was in trouble. But he wasn’t. He simply had to come out of the woods, which was a secure area, to collect the battery. The policemen were to make sure he didn’t talk to anybody about what was happening in the woods. Normally he collected a battery and left one, but this time he didn’t leave any.

from the collection of A.H. Butler

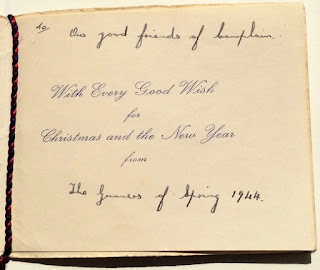

Just before D-Day the soldiers were all issued with French currency, and my mother was given two of these franc notes, which I have in my collection. And then, at Christmas, some soldiers sent my mother Christmas cards, which I’ve got in my collection too. One reads “To Reggie, Michael and Alan,” that is, the children in the household, “with best wishes, John”. And this from the 20th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery: “To our good friends of Cowplain, with every good wish for Christmas and the New Year from the Gunners of Spring, 1944.” That phrase, “the Gunners of Spring”, suggests that soldiers were in Cowplain earlier than I thought: if D-Day was in June, they must have been in the village at the back end of spring.

from the collection of A.H. Butler

That’s how much they thought of us. A couple of things were always in short supply at our house: sugar (we went through an awful lot of sugar), and tea too was very scarce. The soldiers gave my mother either one or two big bags of tea. The tea they were issued with didn’t come in packets, they were in small bags, about nine inches square, and it was full of tea, with a draw cord at the top, to keep it fresh. My mother was given two of these bags as a parting gift. Whether they gave her any other food out of their supply, I don’t know, but I’ll always remember the tea.

My mother would let the soldiers use the bath. Because they had none or very basic washing facilities, a cold shower perhaps, she let them have use of the bath. And one day a lieutenant came to the door, a complete stranger, and said to my mother, “I understand that this is the house that I can have a bath at.” And my mother said yes. And so he left her sixpence to pay for his bath. The soldiers she didn’t charge at all, but she took the sixpence from the lieutenant.

from http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/war/evacuation.htm

Cowplain took evacuees from London and Portsmouth. I can remember an endless stream of cars and wheelbarrows coming out of Portsmouth one evening, when I was a child. Halls and churches put them up. They would accommodate them until they found somewhere to live.

Huts were built in some spare ground in Hart Plain Avenue (where Hart Plain Avenue joined Silvester Road) for more evacuees, but the evacuees never came. They stayed empty for a long time, and then it was decided to turn these wooden huts into a junior school, because we had no junior school in the village, and when the war started, it was overwhelmed by children.

I’d been moved to the senior school. In Cowplain you had a huge great senior school that had a catchment area of Waterlooville, Purbrook, Denmead, Widley and went as far as Rowland’s Castle but didn’t include Havant. It was a funny old radius actually: it went to the top of Portsdown Hill. And then the other way it went to Denmead, Hambledon, Horndean, Clanfield, Lovedean. At one time it was mixed, but then they divided it so you had girls in one half, and boys in the other half. Separate provision was made for the girls and boys. There was no contact with girls that I can remember.

When there was an air-raid, we, the juniors, went up to the shelters. And it was a good old walk to get to the air-raid shelters from the school, about 200 hundred yards, and we were allocated the first one, because we couldn’t walk very fast. We were only little tots. And the senior boys went to the classrooms we had just vacated and trusted to the blast walls to protect them. Luckily, it only ever happened once as far as I can remember. We had dummy runs, but there was actually only once we had an air-raid and were evacuated to the shelters.

So there was one air-raid when we were all summoned there, and the other ones were dummy runs. And you had to put your gas mask on, and they were the most unpleasant things going, because they would steam up in no time at all. I would hate to have to wear one in a gas attack. Any rate, it never happened, thank goodness.

These wooden huts, as I say, had been built, and never used, and then, as I say, it was decided to turn them into a junior school. And so about 1942 (yeah, it would have been about 1942), we were moved from the senior school over into the huts. They were terrible. All you had was a big stove in the middle, and it was the job of somebody in the class (there was big buckets of coal there: I think it was coal, it might have been anthracite) to keep these stoves topped up in the winter. And the classrooms were still cold even with the stoves on. We had to wear our coats in class, they were that cold. Because the stoves radiated a little bit of heat, and beyond that, nothing.

I think there are four or five junior schools in that village now. I wouldn’t like to say.

This map shows our house – the red is 14 London Road (that’s the length of our garden) – and the territory the army took over.

Have you got the photograph I took of the bombs? The drawing pins are the bombs we had. One landed on a poultry farm and killed hundreds of chickens, and the other was at the top of Park Lane. See that square building there? That was one of the old tram sheds. Fodens had it – I didn’t know this until recently virtually – and they were storing torpedoes in there, for submarines. Perhaps I didn’t notice them come, or perhaps they all travelled at nighttime, I don’t know, but somebody knew about them, and the Luftwaffe tried to bomb it, and they were just that little bit out: they bombed the other side of the road (the corner of Park Lane), the bottom of our road and a field. We were lucky. They were the only bombs we had in Cowplain.

As I say, the soldiers were often on the move, and the HQ, we found out afterwards, was Southwick House, which was five miles by road. It’s a museum now, with the layout for D-Day.

Of course, D-Day was cancelled at the last minute, because the weather was that bad. The weather was blowing a storm and it was just impossible, so D-Day was put back a day to the 6th of June. The weather people were involved for a long time to predict a good day for the invasion, but they got it completely wrong. Meteorology then was not the advanced art it is today.

So they all departed. The village was quite empty of tanks, vehicles and guns. We did have some tanks: there were a lot of Bren Gun Carriers (you had a trailer behind the Bren Gun Carrier, and then a small field gun towing behind the trailer). And they all departed. What made my parents’ property quite attractive, was the very wide piece of grass from the edge of the road to the fence of the house (at one time the Horndean Light Railway tram ran along there), and so they army was able to park their vehicles well off the road. Now it was empty.

It was the evening of the 5th of June and suddenly there were aeroplanes in the sky. We looked up, and there were Airspeed Oxfords (they were mainly Oxfords) towing Horsa gliders. They went over the house and we had a good view from the back of the house because the ground dropped a bit. The woods were three quarters of a mile away, and visibility ceased after the woods. But you can imagine, the sky was full of planes. As far as we could see to our right, and as far as we could see to our left, the whole sky was full of aeroplanes and gliders, spaced quite apart but limitless. That’s when we realised that some action was going to take place.

This was getting dusk, at ten o’clock or eleven o’clock at night, so it wouldn’t be long before it would be dark, and then they would fly across the Channel into France, and the planes would shed their gliders, and the gliders would land with the airborne troops inside them.

Mind you, that happened again several weeks later. They wanted to secure a bridge in Holland. They didn’t succeed actually. They couldn’t secure it and the Germans took the bridge, but they did their best, and again the sky was full of Oxfords and Horsa gliders.

Further reading: http://www.portsmouth.co.uk/news/defence/horndean-s-wartime-past-1-6573671 – source of Tanks in Horndean and Home Guard pictures.

Coming soon: Bicycle Ride to Love

Posted by Mike Butler

on Friday, 10 June 2016

·

A ringing bell signals the start.

Eddie Little: Manchester Jazz Society, 8th of June, 2016...

Mike White (from the floor): 9th of June.

Eddie: I beg your pardon. 9th June. And this evening it’s Mike Butler, talking about Michael Garrick, Mike Westbrook, and a deep English jazz.

I chose the subject mainly because I wanted to share a great interview Michael Garrick gave me in March 2006. And it seemed natural to couple him with Mike Westbrook, who I also interviewed, circa October 1998, but the transcript of that interview is lost – one day all the contents of my floppy disc vanished.

Off: Oh!

It happens. So I have a hard copy of the finished piece, but it seems fairly run of the mill stuff. So there’s going to a bit more direct quotation from Michael Garrick than Mike Westbrook tonight.

Perhaps the fact that one is a Michael and the other is a Mike is significant. The rule is, the younger you are, the more formal your moniker, and then, as you mature, you earn a certain chummy informality. It takes determination to hold onto Michael, as I know, and implies a certain hankering after respectability. Mikes however are… Well, Mikes go with the flow. And I think you can hear the difference in the music.

Michael Garrick

Mike Westbrook

Mike Westbrook

Both men are pianists, composers, arrangers and band leaders associated with what we retrospectively know as Jazz Britannia. Michael Garrick was born in Enfield, on the 30th May 1933, and Mike Westbrook was born in High Wycombe on the 21st March, 1936. Only three years separate them, although Garrick seems much the senior figure. Jazz Britannia, a term coined by the BBC, is apt, because both in their own way brought an English sensibility to jazz, which up to then was thought largely to be a North American activity.

‘Deep English’? Well Englishness is problematic, as I hope to show. But before I attempt to disentangle the English stain, it might be best to start with the much more uncomplicated North American influence. Duke Ellington was the household god of Garrick and Westbrook, as he was to every musician who aspired to make jazz a serious art-form. And what of tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, a staple of the Duke Ellington band between 1940 and 1943? My first selection is ‘Webster’s Mood’ by the Michael Garrick Septet. Joe Harriott and Tony Coe take the solos….

‘Webster’s Mood’ (Garrick)… 6.52

Here’s what Michael Garrick told me about it.

“I wrote that the day after I heard Ben Webster live, in London. I’d heard a record of him, with Oscar Peterson, but then when you encounter the real thing, it’s quite different. So I used to practise the piano in a rehearsal studio in Oxford Circus. I just went in as usual – you pay whatever it was; it was about 2/6 for an hour, I think – and just began playing that tune. You play the first phrase (“What’s this?”) and follow it. Then I realised I had a blues. But it was a blues with different changes. It had minor chords in the middle which a normal blues doesn’t have. And the whole movement of it, with that majestic, stately, slowish sureness about it. And I thought, this is from Ben Webster.”

The line-up is Michael Garrick, piano, Ian Carr, trumpet, Don Rendell, saxophone, Dave Green on bass and Trevor Tomkins, drums. As I mentioned, the soloists are Joe Harriott on alto saxophone and Tony Coe on tenor saxophone. It comes from the LP Black Marigolds, and was recorded in January or February, 1966.

It’s as much a tribute to Joe Harriott now, as it is to Ben Webster, I say. Garrick: “Yes, that’s true. Although lots of people have played it. Don Rendell was on that session but he didn’t solo on that particular piece because you were constrained by time. You don’t want the track to go on forever. Which is a great shame. Because on gigs – we did gig that sextet – everybody would solo on it, but then the piece would last a quarter of an hour. And in those days, on LPs, that would have filled almost one side. The producer would say, “It would be better if that one was shorter.” And of course, it is different too, when you’re live with people living and breathing in front of you, as long as they’re being interesting then it doesn’t matter if they go on for ages. But when you’re listening at home and you put a CD on, it’s quite different. You need conciseness.”

Second track, Mike Westbrook’s take on Lionel Hampton’s ‘Flying Home’, which is crowded with incident. John Surman leads on baritone sax…

‘Flying Home’ (Westbrook)… 4:20

A shot of the Concert Band circa '67, with (l to r), Harry Miller, Mike Osborne, John Surman

Mike White: What year is that?

1969, I think.

If Mike Westbrook spent the rest of his career avoiding jazz cliches, it’s because he used them all up on ‘Flying Home’. [Profound silence. Mike: “Oh oh!” Eddie and Eva dutifully laugh.] It comes from Release, a 1969 album by The Mike Westbrook Concert Band on Deram. After John Surman, Malcolm Griffiths takes the trombone solo and Nisar Ahmed, otherwise George, Khan is getting all hysterical attempting to channel the spirit of Coleman Hawkins. Alan Jackson is the unruly drummer.

And here is Michael Garrick’s tribute to …. Well, you can probably guess who. The title is ‘Mrs Marietta Clinkscales’, which is a clue when you know that Mrs Marietta Clinkscales operated as a piano teacher in the Washington D.C. area in the early decades of the 20th century.

‘Mrs Marietta Clinkscales’ (Garrick)… 7:31

‘Mrs Marietta Clinkscales’ comes from Michael Garrick’s ‘A Life of Duke’, commissioned for the 20th International Ellington Conference in London, May 2008. Were you there, Peter?

Peter Caswell: Yeah. And Delia.

A Shakespearian cadence was added to the album release on Jazz Academy, Garrick’s own label: Lady of the Aurian Wood, subtitled ‘A Magic Life of Duke’. The singer is Norma Winstone. The phrase she quotes, “Don’t do that, Henry”, is, of course, culturally specific, despite the USA accent elsewhere. “Don’t do that, Henry”, I needn’t explain, is the running refrain of the celebrated monologue with Joyce Grenfell as the nursery school teacher. Just what Henry is doing is never specified.

Likewise, Ellington tributes are sprinkled through Westbrook’s career. Notably, On Duke’s Birthday, written to mark the tenth anniversary of Ellington’s death in 1974, and possibly a more meticulous, mature reworking of an early jazz inspiration than ‘Flying Home’. It’s not included here because of time limitations and because I don’t have the CD.

Instead let’s pursue the English theme. The third edition of The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD has this to say in the Westbrook entry: “Westbrook belongs to a long-standing English musical tradition one associates (though Westbrook is from semi-rural High Wycombe) with the Lancashire Catholic background out of which John Lennon emerged (and to which novelist/composer Anthony Burgess has paid tribute)…” Now while you’re thinking about that, and if anyone can tell me what it means I’d be grateful, the next selection is ‘Waltz (for Joanna)’ from the 1969 double album, Marching Song by the Mike Westbrook Concert Band.

‘Waltz’ (Westbrook)… 5:51

Marching Song is a suite on the theme of World War 1 – Westbrook served his national service in Germany in the early fifties when whole swathes of the country were bomb sites – and ‘Waltz’ is a pretty interlude amid the angry turbulence elsewhere, but listening to it then, I think a bit of the turbulence does creep in. Tommy is in the trenches thinking of his sweetheart back home. It’s an early vehicle for John Surman’s lyrical soprano sax. Sometimes the arrangements recall Gil Evans, but Marching Song, I think, is jazz with a very English identity, about a national cataclysm.

Garrick again: “Right from the earliest times, when I was still in college in the fifties, it struck me that jazz was obviously the next step forward in serious music. Because it engages in time. Time and pulse and swing. That element, which so far, in so-called classical music, just didn’t exist. That was the new thing – the freedom in relation to time, which didn’t exist before. And so therefore it seemed to me then, this is a completely new way of taking music forward. So I thought people should be educated in it. That’s been my stance ever since.”

It might be significant that neither man has a formal music education. Westbrook studied art at Plymouth College of Art, whereas Garrick studied English at London University. And Shake Keane, who played trumpet in Garrick’s group, also studied English at London University. “You see Shake Keane was a poet, and he came to England later than Joe Harriott. They didn’t know each other, because he came from St Vincent. He came here to study English at University College, London, which is where I was. I was unaware of him then, although we were at the same college. He didn’t put in much time there, and in the end he pulled out, after his second year…

“So when we did meet, which was at the Marquee Club, Wardour Street, where my quartet and his quintet played opposite each other every week, Saturday night, 1958-59… At the same time I was asked to do this Poetry and Jazz thing, and I had a quartet, which went down to a trio, that’s right. We had a trio and I said, ‘Shake, would you like to play with us at this Poetry and Jazz thing with Spike Milligan and Laurie Lee and Dannie Abse?’ And so he played with us, and he was totally sympathetic to the idea of poetry and jazz, being a writer himself.” [‘Shake’, incidentally, is short for Shakespeare; his other name is Ellsworth.]

It’s poignant to think that 400 people had to be turned away from the first Poetry and Jazz In Concert event at Hampstead Town Hall on February 4th, 1961. The success led to a follow-up at the Royal Festival Hall and then to a concert at Belgrade Theatre, Coventry, which marked the debut of the Michael Garrick Trio with Shake Keane. Dates at Cheltenham, Birmingham and Oxford followed, and the Michael Garrick Trio expanded into the Michael Garrick Quintet, with Shake Keane and Joe Harriott as full members. They participated in Centre 42 events. Centre 42, er, was an attempt by the Trades Union Congress to devolve culture and art into the regions, with the playwright Arnold Wesker as a guiding force. It was crucial to the development of the folk music revival, but that’s by the by. Poetry and Jazz In Concert spawned more than 250 concerts, two LPs on the Argo label, and a poetry book, which you can pass around. [Produces Poems From Poetry & Jazz In Concert, edit. Jeremy Robson, 1969, Panther.]

Jeremy Robson

“The opportunities came. I didn’t invent them. They came along. I thought, oh, this is great. It’s what I’d like to do. Poetry and Jazz for example. A poet called Jeremy Robson was organising poetry and jazz together in the beginning of the sixties and he heard us, and said would I like to work with him? Because he was going to expand and work with other poets. That’s how it happened. Through that came the first Argo recording which has just been reissued, Poetry & Jazz In Concert.”

The Argo records are weighted more to poetry than jazz and only Adrian Mitchell on the first record and Jeremy Robson on the second actually attempt to read to jazz accompaniment. But the jazz and poetry are integral elements, with the jazz as a direct response to the poems. ‘Wedding Hymn’, the next piece we shall hear, was inspired by Dannie Abse’s ‘Epithalamion’ (a tough word to pronounce), a poem for his wife, Joan Abse. Here’s a flavour:

Singing, today I married my white girl,

beautiful in a barley field.

Green on thy finger a grass blade curled.

So with this ring I thee wed,

and send our love to the loveless world

of all the living and all the dead.

’Wedding Hymn’ (Garrick Quintet)… 8:07

The line-up is Joe Harriott, alto sax; Coleridge Goode, bass; Colin Barnes, drums; Shake Keane, flugelhorn; Michael Garrick, piano.

Garrick on Joe Harriott: “Joe Harriott was a Charlie Parker man through and through. He’d been brought up in an orphanage in Jamaica, the Alpha Boys’ School.”

I chip in, “Oh, the one that gave birth to The Ska-talites?”

“That’s right, and not a few others. And they must have been very good teachers there, because he started on clarinet. But when he arrived here, which was in 1951, although I didn’t know him till seven years on… Everyone says he arrived here and he was playing fantastic on arrival. So where he got that from is a mystery. In a home for wayward boys or orphans, accumulating all that knowledge and putting it onto his horn, all the Charlie Parker compositions, for example, just bore him along. That’s the mystery of Joe Harriott.

“And there was this idea about free form. It was then that the Caribbean influence came into his music more. There’s one in particular called ‘Calypso Sketches’. It’s a deliberate calypso thing. [As ‘Calypso’, it appears on Free Form by the Joe Harriott Quintet, Jazzland, JLP49, 1961.] But the other one,” [Abstract by The Joe Harriott Quintet, Columbia 33SX 1477, 1962] “it’s more like a cross between circus music, European impressionism and bebop. They’re wonderful things, the Joe Harriott free form records.”

So how calypso is ‘Calypso Sketches’? In 2004 the Michael Garrick Jazz Orchestra issued a tribute album called Big Band Harriott, so let’s find out.

’Calypso Sketches’ (Garrick)… 4:51

From the sleeve-notes: “To the fore, Martin Hathaway and Quentin Collins (trumpet), Jimmy Adams (trombone) and Gabriel Garrick (trumpet). It’s 2.30am and carnival time. You could say that this one is closest to Joe’s Jamaican roots, but his gaze was always onward and outward.”

More Garrick and Westbrook after the break, shall we say? Thanks guys,

[applause]

* *

OK, to pick up where I left off, and without further ado, so Michael Garrick said: “So Poetry and Jazz got me on that tack, and it also helped my composing immensely, because I found that by taking a poem – not any poem, of course, because you can’t set Shakespeare’s tragedies to jazz too easily – but a lyrical poem, it doesn’t matter whether it’s modern or an ancient ballad, it will give you the mood, it will give you the movement. So you can write music out of the feelings you get from it. That’s how I found I could write original music. I wasn’t thinking, now I’m going a write a blues, or an ‘I’ve Got Rhythm’ type tune. I just look at the poem and let the music come out of it. And so it would lead to different shapes of composition, according to the poem – odd numbers of bars. Most jazz music is written in 8-bar phrases. Instead of adding up to 16 or 32 bars, I might suddenly find I’d got a piece with 19 bars or 21. But then which held together because the starting point in itself held together. And then I found I could do it without poems. Still things would come out odd shapes and so on.”

I said that Englishness is problematic. I said that ‘Webster’s Mood’ is so sublime that, for me, it could go on forever. In fact, whenever I do play it, I have to speedily get up to raise the arm before the next track starts. And if I’m a bit slow, this is what comes on.

’Jazz for Five’ excerpt (Garrick)… 1:23

[John Smith recites to Garrick’s piano:

You are winter

You are a landscape of snow…

And though my arms are not yet ready to hold you

Because of the loosened tenderness of your especial being

I will let the air only vibrate with a small celebration of words

Saying

I love you

You are winter

]

Now can anyone defend that to me?

Eva: Yeah, yeah. [Chuckles elsewhere]

Don Lee: Mike, who was that speaking?

It’s a poet called John Smith, it’s called ‘Jazz For Five’, and what happens next is a series of duets between John Smith, the poet, and the different musicians. I don’t think it’s as good a poem as the Dannie Abse. I don’t believe it. It’s pitched in such ludicrously overblown terms. But I think a bigger stumbling block might be John Smith’s voice.

[Murmurs of agreement]

That awful received pronunciation, which was standard in 1966, but which everybody has thankfully dropped since.

[Titter from Eva. She tells me that there was conversation during the break about my accent.]

All the poets on Poetry and Jazz In Concert possess it to some degree, though none have it as bad as John Smith.

So this is what Garrick had to say about John Smith: [posh, high-pitched voice]: “He has a very interesting voice.

[Mild laughter]

He speaks like that. He lives in South Africa, Cape Town. [Resumes normal voice] And he doesn’t intend to come back. But despite his voice, he was a great character. And he wrote a cantata for us as well, called Mr Smith’s Apocalypse. Although that’s for a choir and organ, and Norma Winstone, and a sextet of musicians. It hasn’t got an orchestra.”

And I chip in. I say, “I did hear it one time, and I found it a bit heavy going actually.”

“Oh it is. It’s very heavy going, I promise you. But then again I thought what he was trying to say was something that should be said. You call to God for help when you really need help and where is he? Gone on holiday. So the only answer is, if you want something like a god, you’ve got to look for him in a human being. You won’t find him anywhere else. That was the theme of it. It was good fun though. I know it’s heavy going. And the words were so dense, that there was very little room for jazz improvisation. But we did get some in. It’s always a compromise, you know.”

The Englishness is problematic, because, England being England, a class element always comes into it, of which received pronunciation is the most obvious outward sign. Duke Ellington is alright, but on the UK side, Garrick’s music (and Westbrook’s) are nurtured by secret wellsprings, and these sub-streams are things like art song, George Butterworth, Vaughan Williams and Constant Lambert setting the poems of Li-Po. [Constant Lambert and Li-Po are the antecedent of the Garrick album, The Heart is a Lotus, except that Garrick fills the roles of both Li-Po and Constant Lambert, as lyricist and composer, which is impressive.] Another piece, I think, before we plumb these murky depths further. This is ‘Rustat’s Gravesong’.

[Bass and John Smith speaks… “A blue dusk girl…”]

Oh, sorry guys, we’re getting more John Smith there. It does sound better, doesn’t it? But, OK, I’ll put on ‘Rustat’s Gravesong’.

‘Rustat’s Gravesong’ (Garrick)… 5:14

Yeah, ’Rustat’s Gravesong’ was recorded in a concert with a jazz group and choir at St Paul’s Cathedral in 1968. Providentially, a French TV crew were present, and the short film they made can be found on Youtube. I mailed the clip to selected Society members earlier in the week. But the event was captured on record. A stereo tape machine was found from somewhere and a single microphone was suspended across the chancel directly above the players. The sound is excellent for such primitive resources, and captures well the rarefied atmosphere. The saxophonist is Jim Philip, and I think the sacred dabblings of Jan Garbarek have an earlier precedent in his swirling, plangent tone. “Jazz Praises is an English experience, retelling the American jazz dream in an Anglican setting.” It works because of a refreshing lack of piety, I think. The jazz group, on the evidence of ‘Rustat’s Gravesong’, don’t rein in the ferocity.

To be an artist in England is to be an outsider, but then artists are always outsiders. There’s always this tension in Garrick's work between rebellion and respectability. His tireless work to get jazz accepted on the curriculum of music colleges is entirely creditable, I think. This comes from a letter he wrote in 1989 to the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music: “The classic sources are clear enough by now: Ellington, Armstrong and Parker, to establish a basic triumvirate. And although primarily an American phenomenon, Britain, placed uniquely between the United States and Europe, has produced much that is original and refreshingly different.”

Westbrook, who shares a tradition and an idiom with Garrick, is by far the more anarchic figure. His idol is not Shakespeare but William Blake, the visionary artist whose phantom arises in every radical period of history, and who had a hey-day in the sixties. Shakespeare has been co-opted by the establishment, but William Blake never could. This is a Westbrook setting of a Blake song, and incorporates a Blake poem.

‘Let the Slave’ incorporating ‘The Price of Experience’ (Westbrook)… 11:28

[Off: Phew!]

‘Let the Slave’ incorporating ‘The Price of Experience’. It comes from a Westbrook album called Glad Day and it was Chris Biscoe playing the passionate alto sax, and Westbrook himself reciting ‘The Price of Experience’. And the stentorian lead vocal, declaiming the song, was my introduction to Phil Minton, who, in my mind, knowing him only from Westbrook performances, represented an English ideal. I pictured a big, bearded Old Testament prophet type. And after all, Minton is only one consonant removed from Milton.

Does anyone know Phil Minton?

Bruce Robinson: I know of him only as a sort of free improvising vocalist.

MB: A free improviser is what he is primarily. I think the Westbrook thing is a sideline, and you get a completely different thing with his free jazz gigs. He’s the pioneer of an extreme kind of body music. He plays alongside hardcore free jazz musicians and proceeds to shriek, burp, gasp, moan, whine, hiss, belch, squall, hoot, snort, coo and choke. And sit tight, I’ve got an example here.

[Anticipatory chuckle from Chris Lee and general laughter]

‘Spermin Spunk About’ (Minton)… 1:48

That was ‘Spermin Spunk About’ by the Phil Minton Quartet from Mouthfull of Ecstasy, free settings of Finnegans Wake.

Phil Minton

In England we judge a person by their accent every time they speak or sing. I did it myself with John Smith earlier. It must be said that Phil Minton’s way out of this particular trap is radical and extremely effective.

Now can I hold up, as an exemplar of everything good about British jazz, a track from Garrick’s 1970 album, The Heart is a Lotus called ‘Torrent’? Which I think finds British jazz musicians finally shaking off their inferiority complex and emerging from the shadows of North American jazz.

‘Torrent’ (Garrick)… 3.44

That was Art Themen and Don Rendell sparring on tenor sax and bassist Dave Green and drummer Trevor Tomkins. Says Garrick (back to my interview): “I was really trying to find a way whereby one could take and draw on the energy and – what else? – sheer creativity that came from America, through Ellington, Parker, Louis Armstrong, that great ebullience, that great life force, that together with this other, English landscape, English poetry and so on, which gives another view of the world. I just thought this contrast in itself gives you the creative edge. So, wilfully or not, I’ve gone down that path.”

As for a sense of English landscape, I would have liked to have played ‘Erme Estuary’ from Mike Westbrook’s magisterial The Cortege, but unfortunately I couldn’t track down a CD copy in time. Chris Biscoe, in a separate interview, told me that The Cortege was the best record he’d ever played on.

And talking about a sense of place, here’s an unexpected encounter between Michael Garrick and Jaco Pastorius: –

“I met him in Boston in 1975…”

Voice off: Jaco?

Yeah, this is Garrick talking. “And when he came here in 1975, he came up here to my house in Berkhamsted, and I took him for a ride round the little villages in Hertfordshire, and he was totally knocked out by it. Because he was born in Florida, and the landscape is still a desert there. When I went to the States myself, only the northern bit, on a long train journey, looking out the window, the difference seemed to me – in England you have countryside; America hasn’t those aeons of cultivation that has happened here. And there again it points up a difference. There’s a rawness to that side as opposed to this. This is 1975, by the way, I haven’t been there since (although I am due to go there with my big band at the end of April to play in New York). It struck me then – England is the granddad and America is the tearaway teenager.”

Mike and Kate Westbrook

Now I love Mike Westbrook because he is or was a loyal employer to some of my favourite British musicians. I say ‘was’ because some of my favourite British musicians are dead or retired – Phil Minton, drummer Tony Marsh, saxophonist Chris Biscoe, and I might add guitarist Brian Godding. A change came in Mike Westbrook’s work around the time he met Kate, soon to be his second wife. She introduced a heady element of cabaret and, reflecting her background in experimental theatre, would create a distinct persona for separate performances. And the Westbrook vision expanded outwards, so that a late masterwork like London Bridge is Broken Down, described as A Composition for Voice, Jazz Orchestra and Chamber Orchestra, has sections called’London Bridge’, Wenceslas Square’, ‘Berlin Wall’, ‘Vienna’ and ‘Picardie’ and sets texts by Rene Arcos, Wilhelm Busch, Andrea Chedid, Goethe and Siegfried Sassoon, some in translations by Kate Westbrook. It attempts nothing less than a survey of Europe and its history over the past hundred or so years.

If you’ll forgive a glib observation, I think Michael Garrick would probably be a Brexit man, and Mike Westbrook would be for Remain. And I’ll close with ‘Picardie Six’ which comes from London Bridge.

‘Picardie Six’ (Westbrook) … 6:25

Michael Garrick died on 11 November 2011, after being admitted to hospital with heart problems. Mike Westbrook is alive and well and still composing, as far as I know. Thank you.

[Applause]

Mike and Don Lee talk 'Incredibly Strange Music'.

Posted by Mike Butler

on Sunday, 5 June 2016

·

The text in italics is a memoir of family holidays handwritten on three sides of notepaper by Winifred Butler, found a long time afterwards. Alan Butler, her son, comments and adds his own recollections. As told to Mike Butler II (Winifred is my grandmother, and Alan is my father).

Another day, we were looking for a site by a stream [this is how it starts, so this is evidently a fragment of a larger text], it started to rain and the little stream became a river, we had to move to the roadway. Frank went in one direction, Dad for a British Legion Club and was told he could sleep under the billiard table. Frank came back. He had found a farm which we decided on. The farmer was most kind. He had a little table, a lantern and told us to be very careful. We hung our wet capes and coats on hooks. Two old bedsprings were laid on the floor, a pile of clean sacks and a big pile of straw, and we soon had comfortable beds, all in a row, four adults and five children.

It was our second holiday in the New Forest. This would be 1947, I think. See now, I didn’t want to go. And so as an incentive for me to go, she said my pal could come with me. I could invite my friend along. I would be about 13. They said Les Watford could come, and so Mike [brother] said I want my pal. It was David Eames.

Alan had Les Watford and Mike brought Dave Eames. Frank had made a good trailer and Alan’s bike was the only one suitable [to pull it]…

Uncle Frank had made this trailer, and taken a trial run in it and he didn’t like it. So my dad bought it from him. And I was towing it. We’d just set off, and because it was laden – it had three tents in it plus all the kitchen stuff and it was really piled high – part of the trailer broke.

What happened, see, you had two bicycle wheels. There was a bracket on the box side, an angle bracket, with a hole in it where the spindle went in. But the other side, you had to have a band that went round the edge of the wheel – do you follow? – to carry the other side of the spindle. Well he’d made it at work, in the shipyard, and it was only ever light metal, it wasn’t very thick, and the weight was too great, and it snapped. And so we had to dismantle it and then Dad and I went back to Beaulieu, which was about four or five miles away, to the blacksmith there. And he did a really good job and he didn't charge my Dad that much. It was only about two pounds. But the blacksmith made the hole too small for the spindle, and so my Dad and my Uncle Frank sat there on the edge of the road with their penknives reaming the steel out to make the hole bigger for the spindle to go in. And they did it.

Mike and Alan as boys, or boy scouts

And we’d left our first campsite, and set off for the other side of the Forest, and then it started to rain.

Frank went in one direction, Dad for a British Legion Club and was told he could sleep under the billiard table…

I’d forgotten about the British Legion actually, but we continued and we came to this farm. And, as she says, it was pouring with rain, and so my dad asked this farmer could we go in a barn? And so he said yes. And so we went into this barn, and, as she says, we all bedded down in our sleeping bags in the straw there. And it was dark when we went in, see. We had to use a torch because the farmer wouldn’t give us a lamp with the straw. Any rate, we all managed and bedded down because we were all shattered, and glad to get into a nice, warm sleeping-bag. And in the morning the chickens woke up. We were in this barn, see. Well of course, they didn’t know we were there, and there was a cockerel.

To my surprise a magnificent cockerel looked at us from the rafters, surprise on his face, and opened his beak. “Cock-a… cock-a… cocka-doodledoo” at the third attempt.

The cockerel started his morning chirp, ““Cocka-cocka-doooo!” Because he had the shock of seeing all these people laying there. That is completely true. This cockerel. ““Cocka-cocka-doooo!” At the third attempt actually. That’s how the bird went. It wasn’t full thrust. He just made the “doooo”. That’s what happened. It was in the morning, the crack of dawn. It would be daylight, round about five o’clock or something like that. We were all lying there in our sleeping-bags. I’d forgotten about the mattresses, lined with springs, so some of us had some comfort, with us youngsters on the straw.

[And, just to set it down straight, the party consisted of Win and Henry (parents), Frank and Nell (uncle and aunt), and (junior division) Alan, Mike, Reg, Les Watford and Dave Eames.]

What big appetites Les and Dave had. Our breakfast was a billy can of porridge followed by fried bread sausages, eggs or anything we had. The boys took turns in having the frying pan for a plate. Every day the slices got thinner and marge just a mere scrape.

It was the bank holiday, and of course we’d all eat a lot, and so I had to go with Aunt Nell and Mum, and me with the trailer, into Beaulieu and fill up with loaves.

Henry, Win, Nell and Frank outside 14 London Road, September 1959

One place there was a baker, lovely bread, on a bank holiday weekend we ordered six big loaves. They filled the trailer.

The whole trailer was nearly full up with loaves. And not sliced bread in those days, just ordinary loaves. And my mother, she used to cut a loaf, she used to slice it, that way [gestures horizontal direction]. My mother always cut it that way. And those slices were pristine. They were three-eighths of an inch thick, and straight right the way across. I’ve never seen anyone else cut bread like my mother used to cut it. And she was quite quick at it as well.

Les’s mother gave us extra rations. It was still ration books and Dave’s father worked on buildings and got extra rations of cheese which were very welcome.

Mrs Eames’ husband worked on a building site, and they were given an allocation, more cheese, to make themselves sandwiches, see. And the Watfords kept pigs, but they could not give the meat away. When a pig was slaughtered, there had to be an inspector there, and then the pig was butchered, and part of it was given to them and their next-door neighbour (who was in with them). But they could not give any meat away. That was one of the regulations. But Mrs Watford gave my mum a big gammon. Does she mention that? No, she doesn’t. She just mentions about the cheese.

Rationing finished with the Coronation, that’s 1952. Sweets was the last thing to be rationed. We had it really bad after the War. We were getting Lease Lend from America, and when the war finished that stopped. We were harder up then. My father bred rabbits. He gave a rabbit to each of the family, and that was their Christmas dinner. There were no chickens available. Eggs! 1941, my mother is expecting Reg. It’s the back end of the year, December. Because she was pregnant, she was allocated one egg. One egg! [An interjection: per week?] Nooo! [Per month?] Nooo! Because she was pregnant, she was allocated one egg! So what she did, she got this one egg, and she scrambled it, and she gave half to Mike and half to myself. And when I told Reg this story (because my mother, she’s the one who told me this story), and when I told this story to Reg, he said, “I feel deprived. I should have had that egg!”

When we went camping with just our boys we took a small spade. I found a quiet spot, toilet roll under one arm and we were always careful to leave the turf well patted down.

In those days they gave you instructions. You could camp anywhere in the New Forest but you had to be so far away from running water when you had to use the toilet, which is understandable. And so my father – we’d taken this canvas – and he’d put up a little cover, and there was a hole. I dug the hole. Dug a hole quite deep – it would be about two foot plus deep (they told you what depth to dig the hole) – and a pile of soil beside it. Two posts got knocked in with a board. And so you perched yourself on the board, and did a number two in this hole. And then when you’d finished, you got the spade which was beside there, a folding up spade it was, and you got the spade and you sprinkled some soil over, to stop the flies getting to it. And then when you finished, you filled it all in, and turfed it over. Put the turf back over the top of it.

Any rate, me Mum was always a bit embarrassed, because she was the only lady at this particular time, amongst all these lads, five boys and the father [oh, what happened to Aunt Nell and Uncle Frank?]. And so she went early in the morning and there was a little hole in this canvas and she was peeping out of this canvas there, and lo and behold, a kingfisher landed on the branch right where she was watching. It was the first time she’d ever seen a kingfisher bird. And then he dived out of sight, and then came back with a fish in his beak, and he went to that branch and bashed it, the fish, knocked it unconscious, and flew off. Now I’ve never seen a kingfisher. It’s the one bird I’ve never seen.

Another day, we were really low on food, there was a sign ‘Post Office’. We went in the house, the front room was a big room, a log fire burning, two armchairs by the fire, two huge beautiful cats asleep in them. We asked if there was anywhere to buy food. They said, “A van comes round each week…” Each week! The local shop!

“… and a bus comes once a fortnight…”

Oh blimey! What is the name of the place? The other side of Kirklevington. Ahh! The Ship is there. The Ship. Worsall. There was a friend of your mum’s there in the choir. He lived the other side of Worsall. He’s coming one day into Yarm (he was telling us this story), and there was this man (it was during the week) standing at the bus stop there. And so he stopped. So the man said, “Oh, I’m glad you stopped,” he said. “Can you tell me when the next bus is?” He said, “Yes, Saturday.” This is true, this. He said, “How far is it to the nearest town?” “Oh,” he says, “it’s about four miles away.” He said, “Get in the car, I’m going and I’ll give you a lift.” His lorry had broken down, and there he was wanting to get into town, you know.

A bus comes once a fortnight. Once a fortnight! Blimey, that’s worse than this bloke. Well we cycled on and we were down to some lard and bread and runner beans. We went on and found this van in one of the villages. It carried everything, shelves well stocked with 2 big cans of paraffin hanging on the back on the back. We were then well stocked up and in another village was a fish and chip van. What a lovely smell, and they were very good.

There was another story too, a bit different. We were out cycling one Sunday and we were at Titchfield, down in Fareham there. And there was this fish and chip shop, and there was a big sign up outside, just in chalk: ICE CREAM. And we went in there. And Dad said to us, “Would you all like an ice cream?” See, so he went in there and bought these ice creams. They were about threepence each, something like that. And they were gorgeous! My father wasn’t one for chucking out money, but do you know what he said? “Would you all like another one?”

We all said yes, so he went back into the shop and he bought us another ice cream. So we had two ice creams. Gorgeous! Oh, gorgeous they were!

When the war was over, we went to London by coach.

There’s a lot missing here. Now she didn’t mention the first holiday. The first holiday was, I think, 1945. We went to London by rail. We had to go into Waterloo, and then come back again on a local train. and we went and stayed with relations of my mum, second cousins. When you think of it, her father had 16 brothers and sisters, so there were plenty of cousins to go around. As I say, they were kind, and put us up for the week. They gave a break for my father and a bit of excitement for us. My brother can’t remember their names either. But Mike remembered that the two of us had to sleep in a shed. And Mum, Dad and Reg would have had a bedroom in this little terraced house. I’ve got a feeling we weren’t there a full week. It might have just been five days. We arrived on the Monday and left on the Friday.

And then the next year we went by coach, as Mum quotes here. The first time the coaches might have not been running. Directly after the War, they suspended the Express service to London, and then re-started it. So that could have been the next year. And we stopped in a bed and breakfast near Victoria Station, not far from Westminster Cathedral. It was so strange, because the day we went hunting for Westminster Cathedral, we started in the Westminster Abbey area and got direction after direction, and when we eventually found it, it was only a stone’s throw from our bed and breakfast. We went to Mass, when she found out it was so close, at least once or twice.

That same time there was a very strong gusty wind blowing in London, and we were all walking along a street, and my father was typically smoking a cigarette, and a piece of hot ash blew off the tip of his cigarette and went into his eye. Now you remember that my father wore glasses, and so it went under the glasses and into his eye. It burned straight into his eye. He tried to ignore it, but it must have been agony, and the next day, I remember, he called on an optician. And this optician, he cut the top film of the eye, and removed this piece of ash that was embedded in my father’s eye.

Oh and I got up early in the morning, because my parents were in one bedroom and us three lads were in another room. Reg might even have been with them then, in a small bed. Mike and myself were in our own bedroom. Any rate, one morning I got dressed, and went out wandering, and then this foreign woman stopped me. She came out of her bedroom. I remember she was in her dressing gown. She came out of her bedroom door. What she came out for, I don’t know. But the next thing she collars me, stops me, and then thrusts a pair of shoes in my hand. She thought I was the boot boy! Then she went back to her own bedroom there, after she said something in, more likely, French. I was stunned by this. I just put her shoes back by her door and left.

Does she mention about a holiday in Wales? Reg may remember. Reg was the only one who went with them. They stayed at a farm.

Just outside Monmouth we passed a lane, at the entrance it said, ‘Bed and Breakfast’. Farmer, his wife and son. Reg followed the farmer everywhere, very interested when the little calf had to be fed, the farmer put his arm in a pail of milk and the little animal sucked up the milk up off his fingers. His wife was a wonderful cook, lovely pastry. There were a couple of lads from Australia, one held the cat, the other held the dog. I was sure the cat would scratch the dog’s eyes. I started screaming. Mrs Farmer came in with a washing tea towel and the two pets made a dash for the door. I think we were there for a week.

It might have been just over a week, and it was two guineas a night. Does she mention that? Two guineas a night. That’s two pounds and two shillings. When it came to the end, see, the bill was twelve pounds sixty pence (in our present currency). At that time a tradesman’s wage was fifteen pounds a week.

Well the farmer’s wife panicked. Because she hadn’t handled that much money, see. To the extent that she said to my father, “Now you’ve got to cycle back to Portsmouth, you might need this money, Mr Butler. What I want you to do is when you get home, send me a postal order.” No cheques in those days. My father wouldn’t have a cheque any rate. He wouldn’t go anywhere near a bank. She said, “Send me a postal order for the money.” And my father said to her, he said, “No. I knew how much it was going to cost me when we booked in. And the money is here, set aside for you.” She took the money, and more than likely this thirteen pounds that he gave her was the most she’d seen for a long time, perhaps, in one go. She didn’t want the money. That was what she said to him, “Send me a postal order.” Now they want your money before you go in the door.

She took coupons out of one book only and when Dad asked for the bill she said, “You need not pay me now. Any time you can send the money.” But dad thanked her and said how much we had enjoyed ourselves. We left with a big bag of eating apples. When we arrived there we had hung our dripping wet clothes on the wall and I left my peaked cap with a very good head square folded inside to keep out the rain. (Mum forgot to add that she posted it to her and it was waiting for her when we arrived home.) At that time Alan was in lodgings in Middlesbro’ . (That bit’s correct). Mike working for G.E.C. with Aunt Else looking after him at London Road. He wasn’t! He was working at Vospers at the time.

There was one time when we, Mike and myself, went to stay at Aunt Else in Hart Plain Avenue when Mum and Dad and Reg went away, but it wasn’t this trip, because I was in Middlesbrough when this one happened. I know because I’d just moved up here that year. 1955. Mike was going to go into the RAF, the airforce, to do his National Service, but he’d had the motorcycle accident (he was taking this friend, who was in the Merchant Navy, to Southampton), they changed the job that they had him down for for a desk job, perhaps thinking he wasn’t fit enough to do it, and he objected to a desk job, and went into the Merchant Navy.

I wonder who remembers Dad hiring a boat, petrol driven. We sailed happily along in the middle of the Thames. Along comes a smart boat with crew and the captain put his megaphone to his mouth. “Keep to the right of the river.”

No, I don’t remember. I wasn’t there.

Oh my my. She did very well, and she’s brought back a lot of memories for me, but there’s still mistakes and additions. These were just notes for the book she was going to write.

Win (Gran), Mike (grandson/son), Alan (Dad) circa 80s